Agricultural Transformations to Benefit Canadians and the Climate

Agriculture must be reimagined to reduce food waste and carbon emissions. Allison Penner, Executive Director of Reimagine Agriculture, outlines how the federal government can use policy interventions to make agriculture benefit Canadians and the environment.

Outline of the Problem

The history of food is the history of humanity. For most of our existence, the pursuit of enough food has driven relocation, revolutions and innovation. This drive has yielded incredible successes. Despite our population exceeding 8 billion people, we currently produce enough food to sustain everyone and possess the knowledge to do so sustainably in the long term.

Yet the stark reality contrasts with this potential, as our current food system exhibits staggering inefficiency and resource overuse. Presently 50% of arable land and 70% of freshwater globally is used in the food system with estimations of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from this sector accounting for 25-34% of total emissions. Despite our food production capacity, over 800 million do not have enough food. These challenges are not inherent to meeting production demands, but a result of shifting dietary patterns and increased loss and waste.

Food Waste and Loss

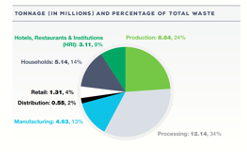

Globally, 1/3 of all food produced is lost or wasted. Canada is a leading contributor to this issue with an annual waste and loss rate of 56%. This problem permeates the entire food supply chain with 80% of the waste occurring before reaching consumers. Each year, every Canadian could be fed for 5 months exclusively with the food wasted annually. It also represents an incredible cost to producers and increases food prices. From an environmental perspective, Canadian food waste generates 56.5 M tonnes of CO2 equivalent emissions each year with the vast majority ending in landfills.

We have the opportunity to mitigate the vast majority of food waste and loss by leveraging available global tools, knowledge and case studies. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12.3 aims to halve global food waste giving rise to Champions 12.3, an international group dedicated to realizing this goal. They propose a ‘target, measure, act’ approach, focusing on setting goals for reduction, tracking food waste across the system and taking necessary action. Its success can be demonstrated in South Korea’s transformation. In 1996, South Korea recycled about 2.6% of food wasted. By 2015, the country now recycles close to 100% of all food wasted. Canada needs to begin by tracking food waste and then establish reduction targets.

Conventional Animal Agriculture

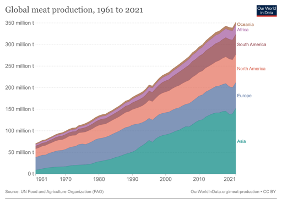

In the last 60 years, when the population has doubled, meat consumption has quadrupled. Creating meat necessitates an inefficient use of resources. A 2018 study by Alon Shepon compared the environmental impact of various animal products to plant products with similar nutritional value, revealing that all animal products were more environmentally costly .Beef, for example, represented a staggering 96% greater environmental cost than plant-based alternatives. Globally, animal agriculture provides less than 1/5 of our calories but utilizes over 80% of agricultural land, contributes more than half of the sector’s air and water pollution, and stands as the leading cause of habitat loss.

Canada is a leading contributor to this trend as the federal government subsidizes a diet rich in animal agriculture. Annually, an estimated $6-8 billion of Canadian agricultural funding predominantly supports animal agriculture. These subsidies promote production through mechanisms such as quota systems that support the production of dairy, eggs and poultry in Canada. This involves setting a target level of production with a fixed selling price. These systems continue, even when production far outstrips demand, leading to dumping the food produced. While farming subsidies play a crucial role in governance, Canada’s current funding model neglects support for small-scale farmers, sustainable production or low carbon products. This propels our high consumption of meat. In 2019, Health Canada released its newest food guide. Focusing on health related evidence-based sources, the guide is plant-focused, with Health Canada also sharing about the environmental benefits of this type of diet. Yet, the food environment in Canada makes following this guide difficult to implement.

Canada can implement a series of policy interventions to address these issues, fostering change in the food system and consumer behaviour. Long term, subsidies need to be shifted towards plant-based agriculture and alternative protein production including cellular agriculture, precision fermentation and plant-based options. Additionally, creating a supportive food environment can involve labelling products with their environmental and health effects and implementing interventions to reduce the cost and barriers to accessing fruits and vegetables. Beyond this, there is a need to have consistent, evidence-based messaging to create understanding of the basic impact of a high meat diet on our environment and health.

Conclusion

The food system not only inefficiently utilizes key resources but also significantly contributes to global climate change and environmental degradation.Yet this challenge can be seen as a significant opportunity. Food waste and the prevalence of high meat diets are very new problems and are not intrinsic to global food production. With the potency of methane, transforming the agricultural system gives us an immediate opportunity to reduce our impact and mitigate climate change. These changes will yield wide-ranging benefits on reducing food prices, alleviating animal suffering, improving our personal health and reducing our global health and disease risk factor.