And Now for the Hard Part: From the ‘What’ to the ‘How’ on Reducing Emissions

We know what the problem is. Now how do we go about implementing solutions? Professor Monica Gattinger explains why climate action is easier said than done, and what this means for Canada.

It’s no secret that Canada isn’t on track to meet its 2030 Paris target. In 2015, Canada recommitted in Paris to reducing emissions 30% from 2005 levels by 2030. In 2017, emissions were down a mere 2% from 2005 levels (from 730 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent to 716).

Making a commitment to reduce emissions turns out to be a lot easier than actually doing it.

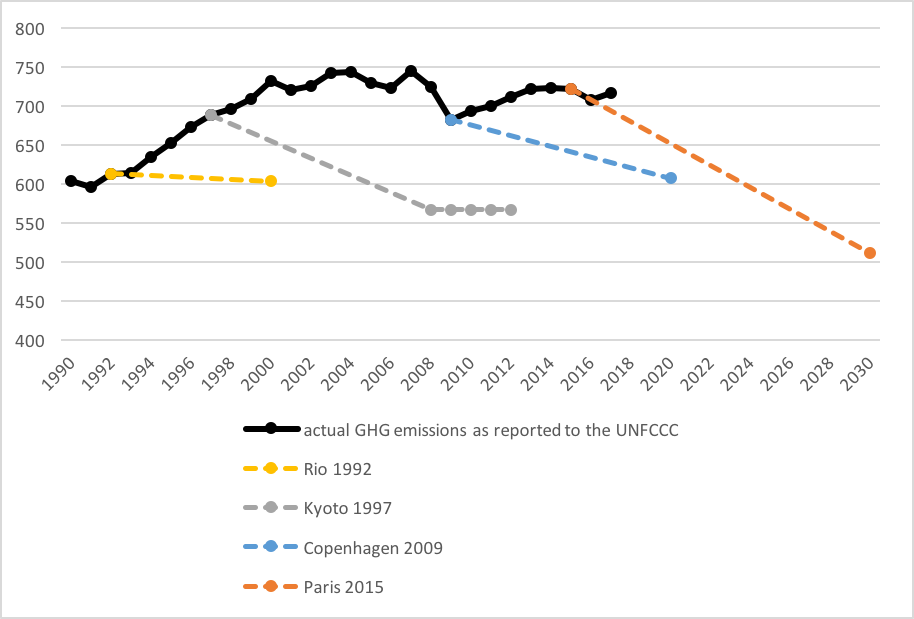

Unfortunately, this is not a new story. As shown in Figure 1, Canada has a long history of overpromising and underdelivering on emissions reductions. From Rio in 1992, to Kyoto in 1997, to Copenhagen in 2009, Canada has repeatedly failed to meet its targets. Paris looks set to be no exception.

Why?

People propose numerous reasons. Many point to emissions from the energy sector – especially the oilsands – as the culprit, others to politicians looking to score points with overambitious commitments. Still others blame political leaders for lacking the courage to follow through on promises.

All of these factors play a role. But there’s another that’s often overlooked: the political and social realities of implementation.

The climate movement has been very successful at getting climate action to the top of government policy agendas – the ‘what’ half of the equation. Moving to the ‘how’ requires paying careful attention to the political and social dimensions of large-scale energy system change.

Take the case of carbon pricing. There is widespread consensus amongst economists that a carbon tax should be a cornerstone of climate policy, but putting one in place is proving much easier said than done. Why?

Because implementing emissions reductions policies is a lot harder in practice than in theory. And in Canada, a federal democracy with a large energy resource base distributed unevenly across the provinces and territories, it is that much more difficult.

When it comes to lowering emissions in Canada, successfully moving from the scientific and technical ‘what’ to the social and political ‘how’ means at least three things.

Understanding the Political and Social Context for Implementation

First, it means coming to grips with the contemporary political and social context for implementation in any policy sector, including climate and energy.

The political environment is more fractured, partisan and polarized globally and within countries and regions. The surge of attention to understanding how group identity, tribalism, and populism shape politics is emblematic of this change. Canada is not immune to these tendencies – as current climate and energy debates amply demonstrate.

What’s more, academic studies reveal that people use ‘motivated reasoning’ when forming their opinions on controversial public issues like climate and energy, selecting evidence that aligns with their world views and values and dismissing information that doesn’t. One of the primary motivations driving this tendency is group affiliation and identity, including partisan political affiliation.

Paradoxically, efforts to ‘educate’ people about issues using ‘the facts’ can backfire, entrenching them more firmly in their positions and further polarizing debates. Repeatedly telling people there is a climate emergency or that a carbon tax is essential may not change their minds – it could even harden them against these ideas.

Successful implementation also means understanding – if not accepting – that climate action may not be the only priority on peoples’ minds. For some, energy affordability, reliability and security, or environmental impacts of energy development beyond the climate, or economic opportunity, jobs and competitiveness, might be higher priorities than climate.

Monica Gattinger

Another key characteristic of the contemporary implementation environment is the decline of public trust in government, industry and experts across western industrialized democracies. The 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer declared ‘trust is in crisis around the world.’ The 2018 Barometer showed that for more than half of respondents, lower trust in media made them unable to identify the truth and to trust government leaders. The 2019 survey revealed a ‘trust gap’ between the informed public and the mass population, with the former more trusting than the latter, where nearly half believe ‘the system is failing them.’

Academic research also underscores that citizens’ deference to authority of various types (elite, government, industry, etc.) has declined over the decades. People are less likely to accept and believe what the ‘experts’ have to say on everything from their health, to the environment, governance and the economy.

At the same time, citizens have a greater desire to be involved in government decisions that affect them. They expect to have a say in all manner of public choices from the international to the national, provincial and local.

This implementation context expands the number of issues needing attention from those looking for ambitious emissions reduction. How to make evidence-informed decisions for the long-term when short-term political imperatives pull in the opposite direction? How to strengthen public confidence in decisions when confidence in decision-making processes may become just as crucial – or even rival – confidence in the substance of decisions? And how to do both of these things in an era of political fragmentation and a time in which the nature of trust itself – who or what people trust, why they trust it and with what level of commitment – is in flux?

Understand that Climate May Not be Peoples’ Only Priority

Successful implementation also means understanding – if not accepting – that climate action may not be the only priority on peoples’ minds. For some, energy affordability, reliability and security, or environmental impacts of energy development beyond the climate, or economic opportunity, jobs and competitiveness, might be higher priorities than climate.

Polling by Positive Energy shows that more than nine in ten Canadians favour increasing energy production from renewable sources, and six in ten support a long-term transition away from fossil fuels. However, this support might not translate to acceptance of the realities of implementation. Positive Energy research examining a rejected wind energy project in St Valentin, Québec revealed that the project failed due to citizen concerns about noise, visual impacts, and impacts on wildlife. Another research study examining the Wuskwatim hydropower facility in Manitoba revealed that some community members were concerned about local environmental impacts on habitat, wildlife and water quality. Of note, climate change mitigation was not the main driver of local attitudes towards either of these renewable energy projects.

Understanding the Political and Social Realities of Large-Scale Energy System Change

Successfully moving from the ‘what’ to the ‘how’ of energy and emissions reduction also means coming to grips with the social and political realities of large-scale energy system change.

A simple thought experiment underscores the challenges.

The federal government has committed to decrease emissions by 80 percent from 2005 levels by 2050. This requires nothing short of a complete transformation of Canada’s energy system. The Trottier Energy Futures Report provides a scenario (8R60a) of what this would entail. Among other things, it would mean cutting Canada’s oil and gas exports in half, converting the transportation fleet to almost entirely electric and hydrogen-fueled vehicles, and, importantly, more than doubling the country’s electric power infrastructure to electrify the energy system.

This last change is vast: the proposed increase in installed electricity capacity equates to building more than one hundred and fifty projects the size of the Site C hydropower project in British Columbia. Could Canada build another 150 Site Cs in three decades when it can barely get one underway?

The point here is not to suggest change is not needed – nor to suggest that new power capacity should come from largescale hydro alone – but rather, to demonstrate how important it is to think through the social and political realities of implementation. This includes community opposition to infrastructure projects for reasons beyond the climate (local environmental impacts, reconciliation with Indigenous peoples), legal challenges that quash approvals or delay construction of projects, capital flight when the prospects of being able to build a project grow dim, and consumer backlash on measures like carbon pricing.

These factors inevitably lead to higher uncertainty and challenge the politically and socially feasible pace of system change of the magnitude required in the coming years.