Bridging Narratives of Social and Environmental Consequences

Naolo Charles, Director of Black Environmental Initiative, discusses the disproportionate impact of pollution on marginalized communities and stresses the importance of proactive measures.

In 1990, a dedicated group of American environmental justice advocates sent a resounding message through what would be remembered as the SWOP letter to ten major environmental organizations. Their message was clear: the environmental sector of that era needed to expand their definition of the environment to include people and communities. The sector apparently overlooked the crucial integration of the social and economic dimensions in their approach to environmental work.

Today, as the world unites to combat the looming threat of climate change, it’s imperative that we don’t lose sight of the ongoing battle against pollution. Excluded communities are on the frontlines of the climate change crisis. Therefore, reducing greenhouse gas emissions is essential for the well-being of our communities. But we must also recognize that pollution’s profound impacts on biodiversity and communities go beyond what can be measured in emissions tallies. These impacts have far-reaching consequences for community health and social outcomes. Many environmental and social impacts that cannot be counted in greenhouse gas emissions do actually count enormously when it comes to communities’ well-being and health. Addressing pollution must be an integral part of our global environmental strategy, standing alongside emissions reduction.

This call to action is rooted in the understanding that mitigating greenhouse gases and combatting pollution can sometimes lead us down separate paths. Take, for example, a nation heavily investing in nuclear energy to reduce emissions. While this approach can lower greenhouse gas emissions because of the low-carbon properties of the production phase of nuclear, it can also lead to increased pollution as nuclear wastes currently have no valid sustainable waste management solution and their cost to society is hardly fully accounted as evidenced by recent developments in Fukushima, where the government is currently releasing nuclear heating water into the ocean.

The only solutions considered by the industry to manage waste that can stay radioactive for thousands of years are the deep geological repositories, which are storage facilities dug deep underground, an immature solution that does not account for the resources required to maintain such facilities over the required time frame and that minimizes the potential risk of ecosystems contamination and future generations environmental burdens.

Pollution’s impact, though diluted in the atmosphere, eventually finds its way back into our bodies through the process of bioaccumulation and this habit that we have in society to consider invisible or unproven threats as non-existent is likely to be the root cause of the spike in cancer and chronic disease rates around the world since the industrial revolution. We are creating chemicals that are not usable in natural processes and we are dying from it. The interconnectedness of our ecosystem emphasizes the need to address environmental issues holistically and to see any harmful pollutants as an urgent threat to tackle.

Unfortunately, the true cost of environmental harm caused by pollution is often borne by vulnerable communities rather than those responsible. Chemicals found in our everyday items, from food to cosmetics, toys, and clothing, pose significant threats to public health and ecological well-being. These threats are not always factored into emissions calculations, making it even more crucial to combat pollution proactively.

Focus on people and biodiversity, not just greenhouse gas emissions

Our fight against climate change must focus on people and on biodiversity because pollution itself threatens our ecosystems, our livelihood and the survival of our species. Mitigating and adapting to climate change must also encompass a commitment to pollution prevention and deeply changing the systems that create that pollution. This includes reforming modern-day consumerism and rethinking the design of consumer products to reduce their social and environmental footprint across their entire life cycle. Ecodesign should actually be an environmental justice priority since all the waste that is not recycled or composted usually ends up in dumps mostly located in poor and excluded communities. This also includes making the right investments today so that tomorrow’s energy grid is more reliant on nature-based energy sources than on energy sources that create waste that cannot be used as inputs in natural processes. To modify our energy grid, society must deconstruct the conditions that are currently maintaining a colonial system and culture of spatial violence, land grabs, and natural assets exploitation in place. A shift toward circular economy principles, along with decolonial frameworks that redistribute land and natural assets to disempowered communities, should guide our global environmental action.

In 2023, sustainability professionals, who have a mandate for holistic and systems thinking embedded in sustainability principles, should lead the way in bridging the narratives of social and environmental consequences stemming from our economic activities. This means breaking down the silos that separate solutions for reforming our system. We need a holistic approach that fosters discussions on sustainability, environmental justice, life cycle thinking, circular economy, community land trust, and similar mutual aid tools within the same spaces. Recognizing the interconnections between these frameworks is essential to addressing the complex challenges facing our world today.

This holistic approach can help us better understand the connections between residing in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods and the impact of pollutants on youth development and educational outcomes for instance.

“Instead of trying to understand which of environmental exposures, genetic pre-conditions and lifestyle factors do lead to high cancer rates and chronic diseases in communities, we should adopt a more holistic approach and investigate their interconnectedness. For instance, we should study how harmful chemicals in workplaces and neighbourhoods can shorten workers and residents lifespans and lock future generations into multi-generational environmental ghettos of cancer and chronic diseases even when they are able to reach upward social mobility. “

Naolo Charles

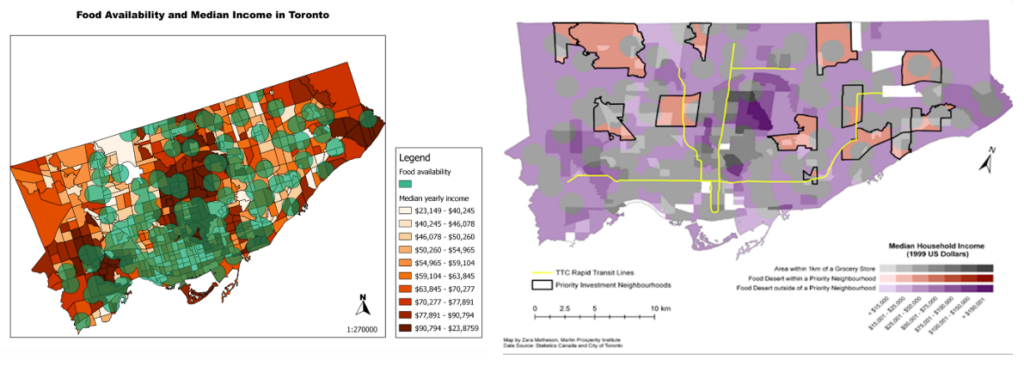

Furthermore, a holistic approach can also help uncover how urban and capitalist practices contribute to “healthy food deserts” in some communities, promoting lifestyle habits that can lead to poor health exacerbated by the compounding effect of unhealthy environments.

In Canada, it is disheartening to acknowledge that racialized communities disproportionately bear the burden of poverty and environmental harm. Over a million low-income Canadians reside within a kilometer of polluting facilities. This grim reality, confirmed by the UN rapporteur for the environment, underscores the urgent need for equitable environmental safeguards.

The Importance of Bill C-226

While Bill C-226 will not allow us to capture all the data that we need to better understand the complex interconnections of impacts in environmental health, it represents a pivotal opportunity for Canada to establish its inaugural environmental justice framework. This bill mandates the development of a national strategy to combat environmental racism, necessitating extensive consultations with diverse stakeholders, including Indigenous communities. Additionally, the bill calls for a comprehensive study examining the intersection of race, socio-economic status, and environmental risk, shedding light on critical connections that must inform policy decisions.

The passage of Bill C-226 would signify a significant milestone in Canada’s environmental justice movement. Through rigorous research, community-driven strategies, and periodic evaluations, this legislation, if properly implemented, has the potential to catalyze enduring progress in rectifying environmental injustices.