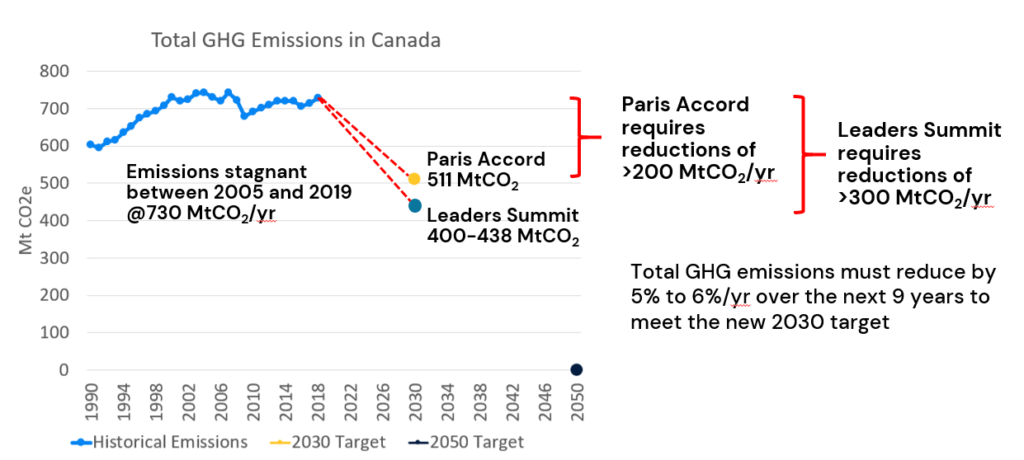

Canada’s emission reduction targets continue to increase – but are our actions actually following suit?

Out of President Biden’s April 2021 Leaders’ Summit on Climate, countries from around the world committed to stronger climate action and underscored the urgency as they stepped up 2030 emission reduction commitments made as recently as 2015 in Paris at COP 21. In line with its peers, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau vowed that Canada would reduce emissions 40% to 45% by 2030 compared with 2005 levels, an increase from previous Conservative and Liberal government pledges of 30% out of Paris and an increase from the 36% pathway illustrated in the Federal budget just a few days prior to the Leaders Summit.

There appears to be growing appreciation of the consensus on the need for reductions and the carbon budget required to maintain “2 degrees” temperature change and the need to achieve 2030 targets and Net-Zero emissions expected from developed countries by 2050. This is seen in sub-national commitments from provincial and municipal governments as well most of the largest public companies, including IT, industry, energy, insurance, and finance, committing to ambitious “science-based” targets and “declarations of emergency.”

However, all this ambition is accompanied by very little evidence of action in line with an imminent “climate emergency” or even implementable plans to meet 2030/40/50 vintage targets. Canada, and its peers, have made commitments to significant ambitious mid-term abatement targets for the past 20 years. However, for the most part, this ambition and commitments made in Rio, Kyoto, Copenhagen even Paris has yielded limited results. Modest reductions in some countries have been far outpaced by emission increases in countries with growing and developing economies.

While improved on a per-capita and per-unit-of-GDP basis, Canada’s Emissions have essentially been stagnant for 20 years. Canada’s current emissions stand at over 700 million tonnes of CO2e per year and will need to reduce by 200 million tonnes to meet the Paris target or over 300 million tonnes to meet the Leaders Summit target. To illustrate the gap in actual emission vs. the most recent target, Canada must eliminate the use of all transportation fuel (-180MTCO2e) and decarbonize the entire electric system (-80MTCO2e) and eliminate all heating fuel use from all buildings (-70MTCO2e) over the next 9.5 years to meet to the 40-45% reduction target.

Our federal government has introduced significant climate policies over the last 6 years. The Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change defines measures to achieve reductions across all sectors of the economy including pricing carbon emissions that will see the price of carbon increase from $40 per tonne CO2e in 2021 to a proposed $170 in 2030. In addition, a clean fuel standard will drive down the emission intensity of liquid fuels and yield reductions of 20 million tonnes of CO2e per year by 2030.

Looking forward, it is clear that we will need substantially more than the above to even meet the Paris target, let alone the latest target. Deep decarbonization high-level pathways are clear and must be driven by action in one or more of 3 broad areas:

- Reduction in the amount of energy used to drive an economy (e.g. GJ/GDP) – an outcome of energy efficiency – for example, codes and standards and energy efficiency programs.

- Reduction in the GHG emissions per unit of energy (e.g. tCO2/GJ) – an outcome of fuel switching such as coal to gas, or gas to low emitting electric, renewables, and low carbon fuels – an outcome of clean carbon fuel standards, renewable portfolio standards, beneficial electrification programs.

- Reduction in the size of the economy (lower GDP) – typically not a viable policy option politically or to create actual reductions. But we have seen in recessions such as 2008-10 and the COVID-19 pandemic. Or at the national level when heavy industry or labor-intensive industry leaves a country to set up in another – known as leakage.

The decarbonization technologies required over the next 10 to 15 years are also as clear as the broad pathways. Further, they are available now, and many are cost-effective. The examples below are 3 of many.

- Transportation electrification can reduce primary energy demand and emissions. Transportation emissions contribute 190 million tonnes of CO2e per year. Over 80% of electricity in Canada comes from non-GHG emitting sources. Electrification of this segment of the economy can reduce energy and operating costs and substantial emissions. The electric vehicle will disrupt the conventional internal combustion engine and demand for refined petroleum products. The only question is “when”? In addition, the advances in managed charging and storage technology will ensure that intermittent renewables are leveraged to the benefit of the ratepayer, the economy and the environment.

- Energy efficiency studies have been carried out in every electricity and natural gas market in North America for the past 25 years. They universally and consistently illustrate significant economically achievable energy reduction potential. In tandem, 25 years of designing and delivering energy efficiency programs illustrate that these savings can be achieved cost-effectively with the use of carefully deployed financial incentives along with IT tools and marketing. Behavioral science shows us clearly that people and businesses respond to inducements more so than penalties or taxes. Canada can achieve a 20-30% reduction in energy use and emissions across all-natural gas and electric systems to the benefit of the ratepayer, the economy and the environment.

- Carbon capture utilization and storage is a key element of all deep decarbonization pathways. The latest Federal budget recognizes this, as does the national and provincial offset systems and the Clean Fuel Standard. This is consistent with the International Energy Agency analysis that says, globally, “reaching net zero will be virtually impossible without CCUS.” Canada has led in illustrating the potential for carbon capture and storage, as illustrated by the project at SaskPower’s coal-fired generating station and Shell’s Quest CCS project, to name a few.

With the broad pathways clear, proven available enabling technology and proven effective regulatory and market mechanisms, we need to move as a country. Reductions of the magnitude committed to in Paris require more than ambition. We need to move with detailed costed plans through 2030. There is a need for strategies and programs requiring analytics and tools and program delivery qualifications that Canadian enterprises have and can deliver.

If we truly believe this is an “emergency,” we need to act like it.

With an appreciation of the detail and plans, we need to communicate and market the approach and not an ideological view but a pragmatic, actionable, and implementable approach. This will require investment in infrastructure. The funding for the infrastructure can come from a carbon tax but not if the proceeds from the tax are simply returned as a dividend on our annual income taxes.

We need to work together, politically and between provinces and sectors. We do not need to pit West vs East, Left vs Right, or our current energy systems and infrastructure against the evolving infrastructure. Both are needed. Transitioning too quickly away from the existing will lead to leakage of emissions as other markets with less abatement ambition pick up the markets we abandon prematurely.

This is not a virtue-signalling competition. If we truly believe this is an “emergency,” we need to act like it. We also need to work internationally, with an appreciation that not every county has the same ability to abate at the same cost and velocity. Emissions in some sectors and countries will rise or fall less than others. These need to be looked at through a global lens, as optimizing emissions reductions in Canada and creating a ripple effect that increases emissions elsewhere is not a solution to the problem.

In Canada, we have the ambition and precedent for doing big things. We have the natural resources and training, and education to be leaders in the current, transitioning and ultimate economy. We have an ambitious commitment to 2050. So before we commit to the next 2030 target, let’s make sure we deliver on the one in front of us, for once. This is doable if we get at it. But time is running out.