Governance Innovation Accelerating Local Climate Action

Karen Farbridge, President at Karen Farbridge & Associates, discusses the history of the energy transition. Today, there is an “implementation gap” in community energy and emissions planning. To address this, cities are adopting new governance models, emphasizing vertical and horizontal integration for effective climate action and overcoming barriers to municipal initiatives.

At the end of the 1800s, U.S. coal and local steam engines powered most of Ontario’s industrial growth. However, as the century turned, energy security was becoming an increasing concern for local politicians and boards of trade in Ontario. Rising coal prices and frequent shortages threatened local prosperity. Municipal leaders across Ontario began to turn their attention to a new energy technology – electricity.

Electricity was produced commercially for the first time in Canada in 1881 and was used to light streetlamps and power local industries in Ottawa. Small electrical systems began to pop up across Ontario. Soon after the turn of the century, most electrical systems in Ontario were owned by municipal governments reflecting their eagerness for their communities to benefit from this new energy technology. These early electricity utilities were the forerunners of the modern Local Distribution Company.

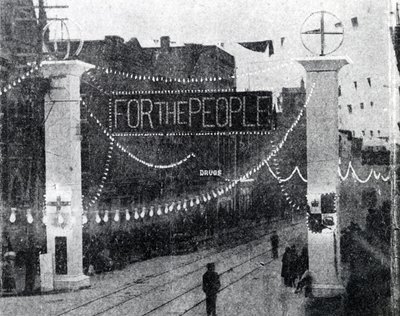

Demand for electricity grew quickly leading to fourteen Ontario cities to launch the “Power for the People” movement. These communities were instrumental in the formation of the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario which centralized the generation and transmission of electricity in the province. Sir Adam Beck, the commission’s first chairman, was an early champion as the mayor of London, Ontario. Abundant and cheap Niagara hydroelectric power arrived in Ontario homes for the first time in 1910.

History teaches us that energy transitions don’t happen on their own. They are driven by human ambition and ingenuity. Without good planning and co-ordination, they can cost more and take longer than they should.

The institutions needed to support the transition to electricity in the early twentieth century did not exist. They had to be invented. As we enter a new energy transition focused on decarbonizing the global economy, new governance models are needed to help navigate the transition as well as operate the energy systems of the future.

“The institutions needed to support the transition to electricity in the early twentieth century did not exist. They had to be invented”

Karen Farbridge

In Canada, local governments are estimated to have direct or indirect control over more than 50% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions within their boundaries. Community energy and emissions planning has emerged in Canada as a governance innovation to help communities navigate the rapid social and technological innovations associated with decarbonization. Community energy planning considers all local energy flows that impact activities within a community, from supply through distribution to its end use by consumers to identify opportunities to reduce energy use and GHG emissions. The practice has arisen both as bottom-up processes from coalitions of local governments, citizens, and stakeholders and through top-down policies from higher levels of governments mandating or incentivizing local governments to engage in community energy and emission plan (CEEP) development.

Yet, despite the remarkable uptake of community energy and emissions planning across Canada, CEEPs face an ‘implementation gap’. Part of the challenge is the wide range of actors that must be engaged for successful implementation. Institutional inertia does not help.

To tackle this implementation gap, municipalities have begun to explore new governance models. Brampton, Oakville, Hamilton, and Burlington along with the Regions of Durham and Waterloo have established “intermediary organizations” designed to engage and hold all actors accountable for achieving CEEP targets within the broader community and within and amongst local governments and utilities.

While the models differ from community to community, the underlying driver is the same: to establish a collaborative governance model to promote vertical integration (i.e., multi-level governance with national and sub-national governments) and horizontal integration (i.e., collaborative governance at the community-scale with businesses, residents, and civil society groups) to help the community fully harness its potential for local climate action. Through collaboration, structural barriers to municipal action are being dismantled including the lack of direct control over major emissions sources, fragmented jurisdiction between public agencies acting within urban areas, insufficient municipal fiscal capacity, and a limited capacity for data-driven decision-making. Collaborative governance is increasingly seen as an important strategy for combating climate change.

“Collaborative governance is increasingly seen as an important strategy for combating climate change”

Karen Farbridge

Like the communities that formed the Power to the People movement more than a hundred years ago, these communities seek to accelerate another energy transition – to benefit local residents and business and, this time, to make a difference on climate change.