MiWay Transit’s Unique Journey to a Zero-Emission Future: Innovation and Resiliency

In this article, Stephen Bacchus gives us an inside look into how Mississauga is using public transit infrastructure updates to meet its zero-emission goals. He explains how they’ve addressed the financial challenges that came up along the way, the ways in which they navigated barriers to updating infrastructure, and the collaborative approaches they took.

The City of Mississauga is charting a bold pathway toward sustainability through its transit agency, MiWay. As cities worldwide grapple with climate change, MiWay’s journey to a zero-emission future offers a compelling and unique narrative of ambition, challenges, and lessons learned. This story, rooted in the city’s 2019 climate emergency declaration, showcases how a transit agency can navigate complex obstacles to decarbonize its fleet, providing a high-level roadmap for others to follow.

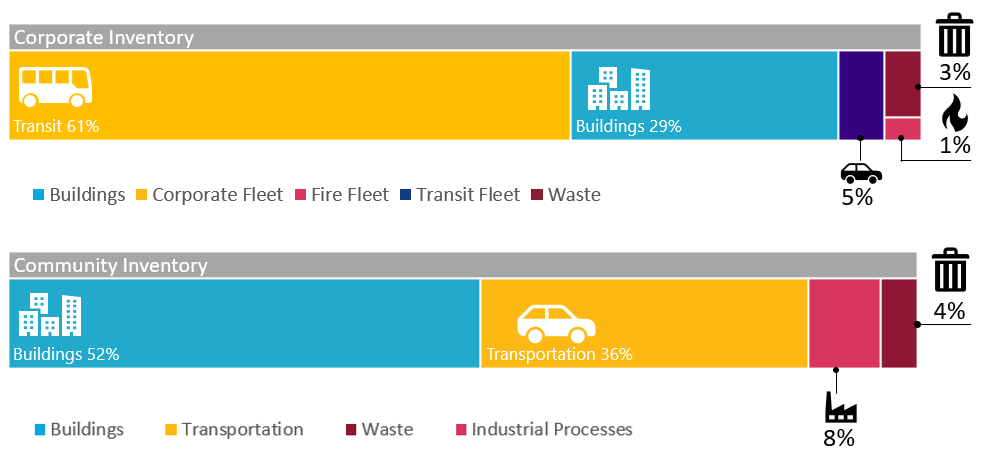

In 2019, Mississauga declared a climate emergency, adopting the Climate Change Action Plan (CCAP) with targets to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 40% by 2030 and 80% by 2050. With transit accounting for roughly 70% of the city’s corporate GHG inventory (70,471 tCO2e) in 2018, decarbonizing MiWay’s fleet became a top priority. MiWay’s strategy blends immediate action with long-term innovation, starting with its non-revenue fleet and extending to its buses. The diagram below shows the corporate and community GHG inventory broken down by service as of 2025.

MiWay’s journey began with the purchase of electric vehicles (EVs) for its non-revenue fleet, including cars, vans, and pickups. Unlike heavy-duty buses, light-duty EV technology was more mature, reducing adoption risks. MiWay installed (10) x Level 2 chargers at its Central Parkway Facility to support these vehicles. The results were encouraging as EVs proved more reliable, with lower operating and maintenance costs, and a longer lifespan compared to traditional gas-powered vehicles. These benefits spurred MiWay to convert now over 70% of its non-revenue fleet to battery-electric vehicles, setting a foundation for broader electrification efforts.

The bus fleet, responsible for the bulk of emissions, presented a greater challenge. In 2019, MiWay stopped purchasing conventional diesel buses, which emit roughly 107 tCO2e annually per bus, and focused on hybrid-electric buses. These buses, combining diesel engines with electric motors, use about 30% less fuel, reducing emissions significantly. By June 2025, more than 55% of MiWay’s bus fleet were hybrid-electric, with plans to reach more than 70% by 2026.

MiWay’s hybrid-electric bus strategy serves as a bridge to zero-emission technologies as both technology include high voltage subsystems. MiWay is piloting (15) x battery-electric buses (BEBs) for delivery in 2027 at its Central Parkway Garage, and (10) x hydrogen fuel cell electric buses (FCEBs) by 2026 at its Malton Garage. These pilots will inform the future fleet mix, balancing range, cost, and infrastructure needs. So why is this a unique journey MiWay is on? Well, the Hydrogen FCEB project will be the first in Ontario, and largest fleet in Canada upon project completion.

Part 1: Navigating Roadblocks: Challenges in the Transition

The path to zero emissions is had many challenges, from financial pressures to technical limitations. MiWay’s experience highlights the complexity of this transformation.

Financial Challenges – The Rising Cost of Progress

The transition to zero-emission buses was met with significant financial obstacles. Since 2019, the cost of battery-electric buses (BEBs) and hydrogen fuel cell electric buses (FCEBs) had escalated by over 40%, driven by inflation, foreign exchange volatility, and supply chain disruptions. BEBs, for instance, cost more than double their diesel buses, with additional expenses for specialized parts and labor. These rising costs posed financial challenges, as MiWay grappled with balancing budgets while pursuing sustainability. Initially the City was planning to purchase more BEBs, however given the escalating costs, the pilot project was scaled back.

To address this some of the financial challenges, MiWay developed robust business cases to secure external funding, which resulted in over $10 million in federal funding from the Zero Emission Transit Fund (ZETF) to support the procurement of the (10) x FCEBs and associated facility upgrades to store and maintain FCEBs safely. Agencies should look to various funding models that reduce or share financial risk, where high-level project goals can still be met.

Environmental Challenges – The Trade-offs

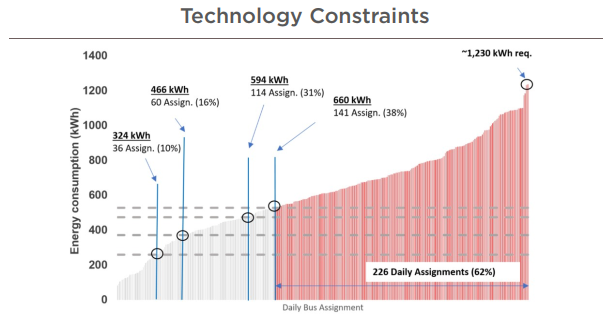

The environmental performance of zero-emission buses presented another set of challenges. BEBs, while promising, may struggle to meet the demands of MiWay’s extensive transit network. Current technology suggest a 1:2 replacement ratio, meaning two BEBs are needed to service a route typically covered by one diesel bus. This inefficiency was exacerbated in cold Canadian winters, where battery range could drop significantly, necessitating diesel-powered cabin heaters. The diagram below based on MiWay’s first electrification feasibility study shows the technology constraints and the impact of range based on MiWay’s existing service profile. Most of existing routes would not be able to be serviced using battery-electric buses alone (before any re-blocking or service optimization).

FCEBs offered a potential solution, boasting a range of over 500 kilometers and refueling times of just 10 minutes compared to 4–6 hours for BEBs. However, the high cost and limited availability of green hydrogen posed additional hurdles. MiWay recognized that both technologies needed real world head-to-head testing to determine their viability within Mississauga’s unique operational context. These pilots are not merely experiments, but critical steps in refining MiWay’s zero-emission strategy. The data collected will inform the optimal fleet mix, balancing BEBs and FCEBs based on route demands, infrastructure readiness, and operational efficiency. During the initial zero-emission bus strategy, a predominant BEB fleet was always the goal, however through careful planning and studies carried out, MiWay has now considered a larger hydrogen FCEB fleet or a mixed fleet scenario.

Agencies should thoughtfully explore all possible options and solutions when solving a particular challenge, even though they may be unconventional or unorthodox. The decision-making process should be collaborative, bringing together groups of staff that affect or are affected by the outcomes of the decisions and solutions. This will require the right people, with the right knowledge, having the right qualifications, to make the right decision. By leveraging the diverse strengths and insights of these staff members, we can feel confident that the decision we ultimately make is well-informed, innovative, and effective, while dealing with competing interests.

Infrastructure Challenges – Space and Scalability

MiWay’s existing garages at Central Parkway and Malton lack the space to accommodate the extensive infrastructure required for zero-emission buses. BEBs require substations, chargers, and battery storage systems and other upgrades, while FCEBs may need electrolysers, dryers, compressors, storage tanks, and fueling stations, none of which could be easily integrated into the constrained real estate of existing facilities. For its BEB pilot, MiWay is maximizing existing space to minimize disruptions. As a result, there was a unique opportunity to store and charge these BEBs using in-depot overhead pantograph charging. For FCEBs, MiWay adopted a “hydrogen-as-a-service” model, outsourcing hydrogen production and delivery via tube trailers to reduce onsite infrastructure needs.

To address similar infrastructure challenges, it is imperative that Agencies work collaboratively with internal teams such as fleet, infrastructure, maintenance, service planning and others to understand the limitations early. In MiWay’s case, a 1:1 bus to charger solution is planned, where future scalability is an option as more than one bus can be used by a singular charger.

Part 2: Lessons Learned and Best Practices

MiWay’s journey has yielded valuable insights for other organizations embarking on similar paths:

Engage with Industry and Foster Collaboration: As a public sector transit agency, gaining information on what the market can offer (and plan to offer) is very valuable. Attend conferences, join webinars, network with others in the same line of work. We are not in competition with one another, but rather we are on a shared journey and path. Information from vendors, suppliers, manufacturers, and consultants who are the ones enabling the transition can provide critical market insights to inform technology choices. Participation in industry committees like the Canadian Urban Transit Association (CUTA) the Ontario Public Transit Association (OPTA) enables knowledge sharing and offer a collaborative platform for information sharing.

Assess Local Context: Evaluating local conditions ensures the selection of appropriate propulsion technologies. From an economic development perspective, the City has created a Hydrogen hub and ecosystem where the City was uniquely positioned to attract manufacturers, suppliers, R&D, and end-users supported by municipal and provincial policy. Conducting a market scan to understand how a successful and reliant supply chain would work, is paramount to the success of your project.

Prioritize Change Management: Transitioning to zero-emission technologies requires comprehensive training, clear role delineation, and stakeholder alignment. MiWay has engaged consultants to manage these aspects effectively as it takes buy-in and strategic leadership from all areas of the organization to be successful. Some of these departments include fleet, facilities, infrastructure, information technology, finance, environment, and others. Identifying all the key stakeholders and establishing their roles and responsibilities early is important.

Part 3: A Vision for Tomorrow

Transitioning to a zero-emission transit fleet is a critical step toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions and enhancing urban air quality, but it involves navigating significant challenges like high costs, infrastructure limitations, and technological uncertainties. Best practices drawn from the experiences of leading transit agencies, provide a roadmap for success, balancing environmental, operational, and economic considerations to achieve a sustainable transit future.