Navigating the Crossroads: Canada’s Environmental Crisis and the Circular Economy Solution

Focusing on a recent study on upcycling food waste, Jury Gualandris, Associate Professor and Director at Ivey Business School, highlights the urgent need for sustainable practices in business and proposes solutions. Policymakers, researchers, and educators have a crucial role in reshaping business practices for a more sustainable future.

In September 2023, numerous regions worldwide experienced severe flooding, resulting in thousands of fatalities and countless injuries. Simultaneously, the summer of 2023 marked the hottest on record in the Northern Hemisphere, leading to droughts and wildfires. These extreme events are primarily attributed to the burning of fossil fuels and environmental pollution. Notably, these events disproportionately affect the most vulnerable and marginalized communities globally.

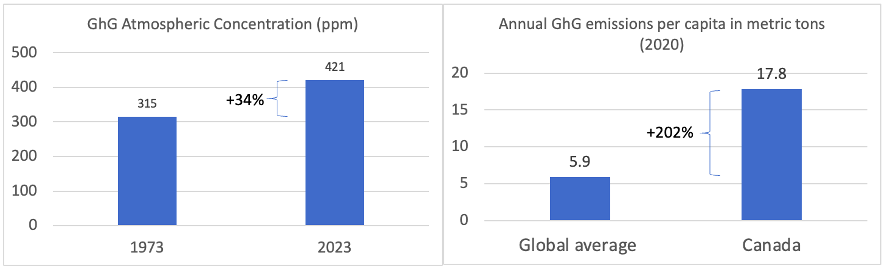

Consider this: 50 years ago, the Earth’s atmosphere contained 315 parts per million (ppm) of greenhouse gas (GHG) molecules. Today, that concentration has soared to 421 ppm. Based on the analysis of air trapped in ancient ice, dating back 800,000 years, we know that GHG concentration in the atmosphere has never been higher than now. In 2020, Canada ranked as the second-largest per capita emitter of GHGs among the top 11 emitting countries, emitting a staggering 17.8 metric tons of GHGs per person, far exceeding the global per capita average of 5.9 metric tons. (Editor’s note: If the recent reports that the extraction of fossil fuels in western Canada being dramatically under-reported by a staggering 64 times prove to be true, then in fact, Canada’s per capita GHG numbers will then be understood to be, by far, the highest in the world. GAP)

Half a century ago, Canada boasted twice the level of biodiversity it currently possesses. Various plant and animal species are now at risk of extinction, with their Canadian populations declining by 42% over the past five decades.

Furthermore, 50 years ago, society practiced more frugal consumption habits and generated significantly less waste. On average, each Canadian now generates 720 kilograms of landfilled waste annually, with certain provinces reaching peaks of 1,007 kilograms.

As a Canadian permanent resident and professor at one of Canada’s leading business schools, I bear a sense of direct responsibility for this concerning environmental track record and its socio-economic consequences. The Canadian Climate Institute has estimated that, by 2025, the Canadian economy will be $25 Billion dollars smaller than if the climate crisis had stabilized in 2015.

When I engage with managers through my research and teaching, I frequently encounter the sentiment that they are committed to implementing sustainable changes, albeit within the confines of maintaining profitability. It’s important to recognize that these managers operate within a global economic system that utterly neglects the natural environment, presenting challenging trade-offs between profit and sustainability. Frequently, the most sustainable businesses find themselves at a competitive disadvantage.

“When I engage with managers through my research and teaching, I frequently encounter the sentiment that they are committed to implementing sustainable changes, albeit within the confines of maintaining profitability.”

Jury Gualandris

To address these trade-offs, policymakers must implement measures such as carbon pricing, extended producer responsibilities, and more conscientious public procurement practices. Simultaneously, researchers and educators like myself must reshape the beliefs and decision-making tools that underlie unsustainable business practices. My research and teaching endeavors, thus, shed light on how companies can effectively reduce GHG emissions, biodiversity loss, and waste simultaneously.

In a recent study conducted with Dr. Sourabh Jain, we offer guidance on how to harness wasted resources for the benefit of both society and the natural environment, with a particular focus on food waste. Astonishingly, nearly 58% of the total food produced in Canada is discarded as surplus (12%), unavoidable residues (39%), and post-consumer leftovers (7%).

We initiated our research with the fundamental premise that there is no waste in nature. In natural systems, when a leaf falls from a tree, it nourishes the forest. For billions of years, nature has demonstrated its ability to regenerate. Waste, in essence, represents a valuable resource that is out of place, time, or condition.

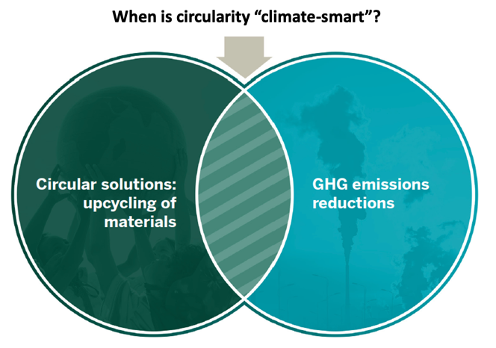

Our study delves deep into the workings of a circular economy, where materials are never wasted, as resources discarded by one company become the raw materials for another. We examined over 80 Canadian companies that upcycle food discards into a diverse array of products, from cookies made from spent grains and fruit residues to natural cosmetics, protein powders, nutrient-rich compost, and green energy. Our central questions were whether these upcycled products are environmentally sustainable and how their circular operations and supply chains must be configured to achieve such outcome.

Through life cycle assessments and simulations, we uncovered that upcycling food discards for human consumption (e.g., cookies, powders, cosmetics) can sometimes result in higher GHG emissions than feeding these discards to animals or utilizing anaerobic digesters. Importantly, we identified four specific conditions under which upcycling becomes ecologically beneficial:

- The total transportation distance from the point of “waste” collection to the point of sale, including intermediary transportation to and from processing and manufacturing facilities, should be less than 300 kilometers.

- The total energy intensity of processing and manufacturing equipment used throughout the upcycling process must be lower than 1,500 kilowatt-hours per ton of processed material.

- The GHG intensity of the energy used for upcycling should mirror that of Ontario and Quebec, ranging from 1.5 to 25 grams of GHG emissions per kilowatt-hour of electricity.

- The quality of upcycled products should be at least 80% comparable to the quality of the virgin products that upcycling displaces, particularly in terms of nutrients and fibers.

Surprisingly, some of the analyzed companies, like Still Good, 123 Sante, and TriCycle, met these specifications, producing and marketing upcycled products that outperform their competition both economically and ecologically.

Our findings underscore the importance of building localized circular systems, investing in increasingly efficient processing technologies, transitioning to greener energy grids, and maintaining functional quality and substitutability with traditional market products that could be replaced by the new generation of upcycled products.

The ecological sustainability and economic competitiveness of Canadian companies hinge on developing new capabilities related to efficient natural resource utilization and innovative resource upcycling. If businesses continue to deplete natural resources without regeneration, their production will ultimately cease. Our study offers solutions for the food sector, and ongoing research at the Ivey Centre for Building Sustainable Value is extending these insights to other industries and materials, such as polycotton in textiles and wood in construction.

Now, more than ever, we must prioritize ecological limits and natural cycles, and then seek economically viable ways to operate within those limits. We have no time to waste.