Not Just a Bad Fire Season: A Personal Wake-Up Call for a Warming World

When a wildfire came within a kilometer of the home of our Clean50 Director, Megan Aoki, in Shiningbank, Alberta, it reshaped her understanding of safety, resilience, and the realities of a changing climate. What began as a personal crisis unfolded into a firsthand experience of the growing intensity of wildfire seasons, driven by environmental and human factors. Her story is both a reflection on her wildfire experience, and a call to act before these events become the new normal.

A Night of Uncertainty

We all have those moments that become fixed in memory – the ones that rearrange your priorities, rewrite your fears, and stay with you long after that instant has passed. Mine came in the middle of the night, from thousands of miles away.

At 1:00 a.m. on May 6th, 2023, I got a text from my husband: A wildfire had started close to our home in Shiningbank, Alberta in Yellowhead County – our idyllic quarter section (160 acres) of forest, grasslands, and a small creek, two hours west of Edmonton and two hours east of Jasper. Home to whitetail deer, elk, moose, cougars, wolves, black bear, two dogs, two horses, four humans, and soon, our first child, a baby girl.

In the early hours of my 31st birthday, I read and reread his messages in disbelief. A wildfire was threatening our livelihood. My husband and in-laws were forced to evacuate with our two dogs and two horses. We didn’t have a horse trailer at the time, so my husband and father-in-law did the only thing they could: They saddled up and rode the horses out themselves.

They rode for over six hours, down the highway, while a giant mushroom cloud of smoke filled the sky behind them. The horror of this circumstance unfolded for me through a phone screen in intermittent messages that updated me on what was going on. I felt utterly helpless, imagining our life going up in flames while I was too far away and completely powerless to do a thing other than anxiously await the next text – incredibly fearful of what it might say.

The fire jumped a river valley and a major highway, coming within one kilometer of our home. Local efforts from farmers and homeowners fought to protect what we could. Some homes were saved, others lost. Ultimately, a fortuitous change in wind direction spared our property.

A Changed Landscape

Six days later, with the evacuation order lifted for our area I came back home and truly grasped just how close we’d come to losing everything. The forest, once green and alive, was gone. Only ash and silence remained.

Within a kilometer of our home, many trees still stood, transformed into charcoal-gray husks, while others were scorched silhouettes, imprinted into the white ash below. Walking through the burnt forest areas felt like stepping onto another planet – one devoid of colour, sound, and life. The smell of smoke clung to everything – clothes, skin, even the truck seats, over a month later.

We weren’t out of danger when the flames moved on. Near our home, fires continued to burn underground, following the root systems. The larger fire still raged out of control to the southwest of our property. So, we got to work.

We assembled a DIY fire unit to tow behind our truck – a 250-gallon tank, a water pump, hoses, shovels, and many 5-gallon buckets. For weeks, we crossed the highway daily to patrol the burned areas and douse smouldering hot spots.

You could sense temperature changes as you walked through the forest, indicating areas where fires continued burning underneath the forest soil. If you listened closely, you could hear the faint crackling beneath the forest floor. In some areas, the heat was so intense it melted the soles off my husband’s boots. These were the areas on which we focused, running hose to every hotspot within reach, and carrying buckets by hand to everything beyond. Sometimes, it took upwards of 10 or 15 trips, dumping buckets each time, before the steam stopped rising.

We witnessed several flare-ups. There was one area to which we kept returning day after day, where no matter how tirelessly we worked, going through tank after tank of water, we couldn’t make a dent. This section of forest marked the line between the burn and the forest that had not yet been touched by the flames. Just 30 yards to the south stood one of the last remaining stands of unburned tamarack.

After several days with no noticeable progress to diminish the smouldering fires under the forest floor, we went back in with another full tank of water. Over the downed trees, we ran the full length of our hose into the spot that appeared hottest on that day. Unbelievably, it was then at that very moment we were set up, that the hot spot in front of us erupted into an eight-foot wall of flames extending towards the unburnt tamarack stand.

Within seconds, we had the water pump at full throttle, and we emptied the full tank of water on the fire. By the time the tank was dry, the flames were gone. It was a miraculous stroke of luck – the fact that we were already set up made the difference. Had we had been minutes later, we likely would have been too late. Oddly then, in an area with basically non-existent cell reception, we managed to put a call through to the fire department who then patched the message through to the nearest fire crew in the area, who reached us within minutes and took over from there.

Situations like this kept happening. And with the main fire burning out of control to the south, there were limited fire units available to patrol our area. So, every day, for weeks, we put in long hours – patrolling nearly 14 kilometers in total. We woke early, returned home late, exhausted and coated in ash, reeking of thick, acrid smoke.

For a time, the air quality in Shiningbank was ranked the worst in the world. You couldn’t see the sun – only a dense amber haze that made the whole world feel suspended in time. And the smell – overwhelming, all-consuming – erased everything else.

For 44 days, the threat of an inferno that could destroy us, hovered. It became our new “normal”.

And then came the flood.

In mid-June, six inches of rain fell at our home over a span of eight days, finally slowing the fire’s momentum. On June 18th, 2023, the Shiningbank fire – officially labeled EWF-035 – was finally declared “Being Held”.

Fire to flood, it felt as if nature couldn’t decide how to break us: first fire, then flood.

Source: Yellowhead County Facebook page.

In the end, the Shiningbank fire burned nearly 20,000 hectares — close to 50,000 acres, or the equivalent of 38,000 football fields. And it was one of many. According to the Alberta Government, 2023 saw 1,088 wildfires across the province, burning more than 2.2 million hectares — ten times more than the five-year average — forests roughly the size of 4.5 Prince Edward Islands – or the size of 31 Edmontons. Over 60% were human-caused. A CBC article reported that Alberta Wildfire identifies human-related causes of wildfires can stem from sources such as campfires, recreational activities, agricultural activities, industrial processes, or arson. The remainder are attributed to lightning.

The intense spread of today’s wildfires is largely driven by record dryness and soaring temperatures. Regardless of the causes of fires, once started, the speed and scale of wildfires we see now are strongly influenced by environmental factors. Some public figures have focused heavily on human blame, often overlooking the broader context. While people have long used fire for cooking and warmth in forested areas for thousands of years, only recently have those same behaviors led to such widespread devastation—pointing to a deeper, systemic shift in fire behaviour.

A Growing Pattern

I still don’t know if I’ve fully processed what happened. We moved here to live close to nature, to feel grounded, connected to the land, and in hopes of starting our generational farm. But when nature shifts so dramatically, it reminds you that it’s not something we control.

And yet, our actions are shaping nature.

Wildfires are a natural ecological process that has shaped ecosystems for millennia, aiding in both regeneration and nutrient cycling. However, following decades of burning fossil fuels, clearing forests, and reshaping landscapes, we’ve played a major role in accelerating climate change. These human-made changes now drive climate patterns at a scale far beyond what we saw before the Industrial Revolution.

I am seeing the consequences of those changes – in real time – in the place I call home.

As I write this, we are facing another severe start to fire season in the Prairie provinces. Both Manitoba and Saskatchewan have declared provincial States of Emergency at the end of May due to wildfires. In Alberta, there have already been 549 wildfires this year, 56 of which are currently active, burning a total of 650,000 hectares total in the province. Another area the size of 9 Edmontons gone.

Just 20 kilometers south of our home, the Peers fire continues to burn out of control. Our area was evacuated once already this season, which started on May 29th. The area remained under evacuation alert until June 11th.

The orange skies and smoke brought the memories of 2023 fire season back to the forefront of my mind. Water bombers fly over our house in a steady rhythm, scooping water from nearby Shiningbank Lake. As I sit at my desk, the drone of the water bombers passing every 10 minutes is constant. It’s a sound that I hope doesn’t become too familiar.

I’m not sharing my story just because it happened to me. I’m sharing because it is happening – to more people, more often, and with increasing intensity.

It’s my fear that these two years aren’t just “bad fire seasons.” I fear that this is the new normal. Longer fire seasons. Drier fuels. Faster, more unpredictable wildfires – all directly tied to human-caused climate change.

Some Harsh Facts

Climate change can be hard to fully grasp. Its global scale is overwhelming, and it’s easy to feel individual actions won’t make a difference.

The Government of Canada names carbon dioxide (CO2) as the primary driver of climate change caused by human activity. Through the burning of fossil fuels, CO2 is released in large amounts, and remains in the atmosphere between 300 to 1,000 years. As a result, CO2 emissions continue to influence climate well after it is emitted.

Here are some sobering facts:

- Atmospheric CO2 levels are at their highest in 800,000 years.

- Human activity has caused over 50 times more climate warming than natural changes in solar energy since the Industrial Revolution.

- Contrary to arguments put forward that “swings in temperatures on earth are normal, and we are in one of those warming cycles now”, the truth is that we actually are in the midst of a cycle that should actually be cooling the planet. The Milankovitch cycles theory is ~100 year old, largely settled science – and predict temperature based on the earth’s varying orbit, distance from the sun and angle of the earth’s axis – and show we should be mildly cooling right now.

- Extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and severe, directly linked to disruptions in the climate as a result of human-related emissions.

- Immediate and deep reductions in greenhouse gas emissions are needed because even if emissions stopped today, the planet would remain at an elevated temperature for generations.

A Call to Action, Not to Blame

My experience with wildfire stripped away any illusion that climate change is distant or abstract. It is deeply personal. I’ve felt it in my lungs, carried it in the smell of my clothes, watched it scorch the land we love, and lived with its echo through sleepless nights of uncertainty.

I won’t pretend to have all the answers. But I do know this: Hoping things get better without action isn’t enough. And neither is blame. In the days after the fire, no one asked who was at fault – they simply showed up. Neighbours became allies. Strangers became friends. The strength of our community wasn’t in pointing fingers, but in rolling up sleeves and asking, what needs to be done?

That’s the kind of energy we need now — beyond fire lines and beyond borders. Climate change requires a collective response, one built on cooperation, not division. That means taking responsibility, yes — as individuals, industries, and governments — but doing so with the intention to build, not break each other down.

My daughter will be born into a world very different from the one I grew up in. And yet, I still believe it can be a beautiful one. The land may burn, the skies may darken, but human resilience is real — I’ve seen it firsthand.

So, let’s channel that resilience not just into reacting to disaster, but into preventing the next one. Let’s make the hard choices, the inconvenient ones. Let’s demand more from ourselves and from those in power. Let’s protect what we love — not just because it’s in danger, but because it’s worth saving.

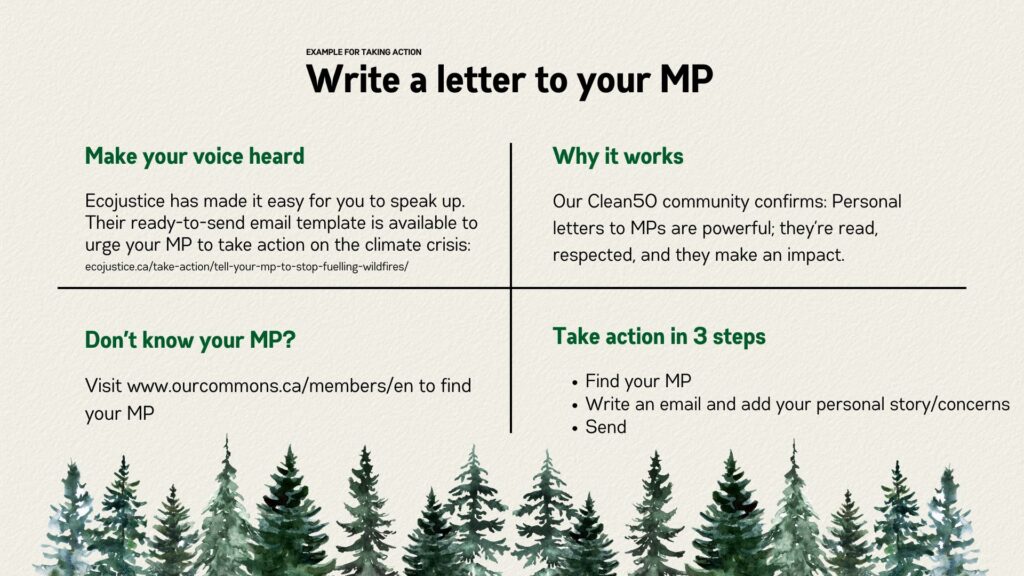

Below, I’ve listed an example of a key way to take action for those looking to take meaningful, informed action as individuals, as communities, and as citizens. Whether it’s changing how we consume, vote, travel, or advocate — change begins with knowing and grows through doing.

Because the fires will come again. But how we face them, and what kind of world we pass on, is still up to us.