The LEAD Project

Projects Sponsor

Energy Futures Lab is clearing the regulatory roadway to upcycling disturbed sites, Canada West Foundation helps put environmental white elephants to work.

Recognizing that entrepreneurs in Alberta aiming to repurpose inactive oil and gas sites for new energy uses faced insurmountable red-tape roadblocks, Energy Futures Lab and Canada West Foundation set about clearing the path. Their LEAD — Leveraging our Energy Assets for Diversification — Project is about filling in regulatory gaps, making it preferable to re-use brownfield rather than greenfield for new energy development.

Currently, there’s no clear regulatory pathway to getting land repurposing projects off the ground. Those who have gotten close to repurposing a site system have found their projects bounced around between regulatory bodies and government ministries.

The LEAD project is not about letting polluters off the hook, but about supporting the best use of land that has already been disturbed. It’s a principle that few would argue, and yet solving the problem is an extremely complex process.

The project’s objectives were simple in theory, but complex in reality. Undaunted, the LEAD Project set out to develop a non-partisan bill that would allow for the safe and responsible redevelopment of oil and gas infrastructure and sites.

Working with stakeholders to clearly understand the system-wide implications of changes to legislation and regulation, and to ensure that any recommendations didn’t create harm for any major stakeholder group was a key component of the project.

Naturally, the LEAD team included legal experts and a jurisdictional scan was performed at the start of the project to determine if there were other regions they could emulate in developing policy recommendations.

Their findings showed that, while other jurisdictions are also struggling with this issue, and some are coming up with creative solutions, there wasn’t an approach they could easily adapt that would align with the existing policy and regulatory schemes. They’d need to start from the ground up.

Understanding that the current government was open to receiving policy recommendations, the LEAD team worked to involve people in the project who had real-world experience and could represent all sides of this issue. The oil and gas liability management system is a fragile one at the moment, and it was recognized that improperly researched interventions could create catastrophic impacts. Stakeholders needed to know that they were not causing more harm than good, so a breadth of knowledge was critical.

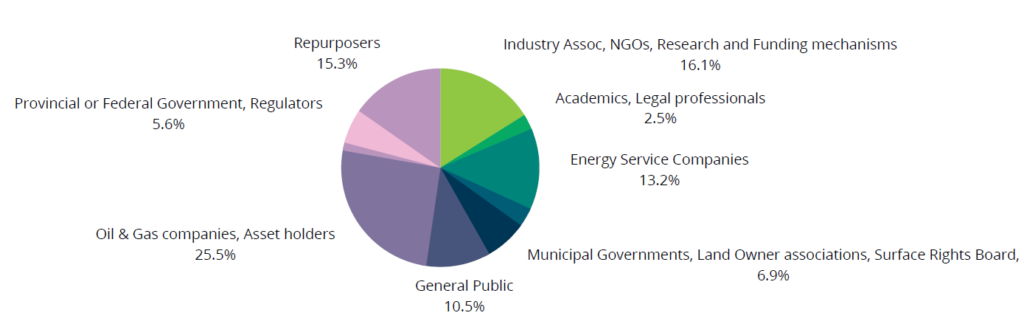

A core project team of over twenty-five people who represented (sometimes unofficially, but could provide perspective from) the oil and gas sector, new energy companies, energy regulators, site remediation companies, think tanks, law firms, energy investment, Indigenous energy developers, landowners and others, was assembled. The team met every two weeks for five months to hammer out the objective, scope definitions, and—ultimately––solutions.

Much work was done, together and independently and after two months, a first draft bill––emulating an existing accepted oil and gas act––was ready for review.

The team then analyzed the draft, discussing and proposing novel solutions to complex problems, dilemmas like “How do you handle the transition of liability?”

Ultimately, three more completely different versions of draft bills were burned through. Getting the letter of the law to match the spirit of the law was tricky. It’s difficult to try to craft legislation that won’t ultimately create unintended adverse impacts for any particular type of stakeholder.

Certainly, conversations were often tense, but the comprehensive process ensured all voices were heard. Tradeoffs were negotiated when necessary, ensuring there were no “deal breakers” in their end product.

The final draft bill that was presented to the government, along with a descriptive report, was shorter, yet impactful. The intention was to open a dialogue between government and stakeholders that would generate awareness and some alignment in industry around this topic.

In order to ensure that the bill and recommendations wouldn’t be seen as partisan, the official opposition party was also consulted, so that they could understand how the bill and report had been developed, and what its objective was. As a result, both government and opposition have shown support for the contents. This helps ensure that the results will face less opposition, and also have durability if there is a change in government.

An appendix attached to the report shares mistakes made and wrong pathways taken and why, ultimately, each was rejected. This is an unusual gesture, but, in the spirit in which the bill was developed, the LEAD team felt it was critical to include any information that might prevent others (including government) from falling down the same rabbit holes.

This type of project is not about quick, near-miraculous technological fixes and it doesn’t generate hard metrics but there are a number of lines of evidence that point to LEAD’s success.

First, as a result of that report and bill, the LEAD team received a positive response and follow-up from the Government of Alberta Minister of Energy— Minister Sonya Savage. She directed several of her staff to continue working with the team, and the direction that the ministry is moving on several files suggests the recommendations LEAD provided, and the conversations that ensued have been helpful.

The LEAD team was able to share their results with a broad range of stakeholders through workshops held along the way – engaging over 120 people in discussion about both the problem and the solution – many of whom will pass on these ideas to others in their organizations and wider circles.

There’s been a lot of media buzz about the project, with op-eds in the Calgary Herald, Edmonton Journal, the London Free Press, and the Daily Oil Bulletin and picked up by msn.com, industry magazines and other media outlets.

The breadth of the core project team, the vast expertise employed and the frankness—and openness—the team and the stakeholders brought to the many group discussions as well as the profound complexity of the issues tackled should serve as inspiration to those addressing similar problems.

It is tempting to think that fixing environmental problems can be left up to flashy technological solutions but, as this project shows, sometimes what needs to be engineered is the conditions necessary to enable technology.

Not all other problems confronting other provinces, or indeed Alberta will mirror this one but what the LEAD Project clearly demonstrates is that even what may seem like intractable difficulties can be chipped away if you can bring together the right combination of people and process.