Resilient Agriculture: Low Carbon and So Much More

As climate and trade shocks expose the fragility of Canada’s food system, resilient agriculture is emerging as both a climate solution and an economic necessity. Beth Hunter argues that agricultural resilience must be understood as an economic, social, and ecological system—not merely a carbon accounting exercise. Drawing on the work of FoodBridge, she contends that climate-smart farming succeeds only when farmers are supported through viable markets, regional collaboration, and shared responsibility across food companies, finance, and policy. Hunter emphasizes that soil health, crop diversity, and local knowledge build resilience to climate shocks and trade volatility alike, and that scaling regenerative practices depends on aligning incentives, strengthening farmer-to-farmer learning, and grounding climate ambition in financial reality.

A few years ago, my friend and mentor Hal Hamilton, co-founder of the Sustainable Food Lab, invited me to join him on a series of interviews. Hal wanted to figure out how move beyond the smattering of sustainable agriculture pilot projects on the landscape and get to scale. I was on sabbatical from my job at the McConnell Foundation, looking to get out of the fast lane and reflect. From Hal’s perch in Vermont and mine in France, we reached out to farmers, agronomists, local and global businesses, researchers, non-profit leaders and philanthropists from around North America and Europe. We began just as COVID-19 hit, which meant people were unusually available and we ended up conducting some fifty online interviews.

We initially framed the project around soil carbon sequestration but quickly realized that was far too narrow and didn’t resonate well in the food and farming community. We shifted to calling it “better farming systems”, testing the idea of how regional and global multi-stakeholder teams could accelerate system change. While the concept itself didn’t see the light of day, its embers did. For Hal, it fed into the brilliant Scale Lab and its tools available on the Sustainable Food Lab website. For me, it laid the groundwork for what became FoodBridge, the non-profit I now lead.

Agricultural Climate Solutions

In 2021, research by Nature United’s Ronnie Drever and others demonstrated the critical role that agriculture plays in carbon emissions as well as the (slow, hard to measure) potential for healthy soils to sequester carbon, estimating that 48% of the 2030 opportunities to reduce GHG emissions in Canada using natural climate solutions come from agriculture-related activities like cover crops, biochar, nutrient management and planting trees on farmland.

Meanwhile on the global scene, in the wake of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change, a growing group of companies set targets to achieve net zero emissions by 2050, with initiatives including the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol, and the Value Change Initiative setting frameworks and defining best practices for meeting climate targets.

The Regenerative Agriculture Wave

The seeds for FoodBridge were planted just as the ‘regenerative wave’ was building. While regenerative agriculture began in the 1970 with the Rodale Institute’s vision to build on organics and go beyond sustainability, it took a mainstream turn in the early 2020s when General Mills, PepsiCo and Nestlé launched large-scale regenerative agriculture programs.

970 with the Rodale Institute’s vision to build on organics and go beyond sustainability, it took a mainstream turn in the early 2020s when General Mills, PepsiCo and Nestlé launched large-scale regenerative agriculture programs.

Regenerative agriculture seeks to rebuild soil health and biodiversity using practices like diverse crop rotations; keeping soil covered with winter crops, cover crops, intercrops, and perennials; and reducing chemical pesticides and fertilizers. More holistic approaches integrate livestock and social justice, and “regenerative organic” combines organic and regenerative methods.

Whether company commitments are about net emissions reductions or sourcing acres using regenerative practices, regionally-anchored work is needed to operationalize bold targets. FoodBridge was launched in 2021 to build bold collaborations for resilient, diverse, sustainable and regenerative food and farming, with place-based work focused on eastern Canada and national research and convening activities.

We work for change at scale in mainstream agriculture while also supporting the growth of organic farming and other holistic approaches. We partner with large food companies that have climate or regenerative agriculture or nature goals as well as smaller ones focusing on local food or packaging. And because the challenge is too big for any single organization, we’re convening a community of learning and action for Canadian non-profits working with food companies.

Using the Tariff Crisis to Build Resilience

Recent tariff threats and trade uncertainties south of the border have hit hard for a sector which is deeply connected to the US economy, and (temporarily, we believe) kicked ‘sustainability’ down on the list of priorities.

In the spirit of never letting a good crisis go to waste, these challenges have helped us understand the many facets of the resilience. Resilience is about diversifying markets both within Canada and overseas, but also gets built with healthy soils that absorb water in floods and store moisture in droughts. Resilience grows with a broader diversity of crops to temper the impact of commodity price swings and break pest cycles, and deepens through on-farm biodiversity features like shelterbelts, pollinator strips, and riparian buffers.

Financial, Technical and Social Supports for Farmers

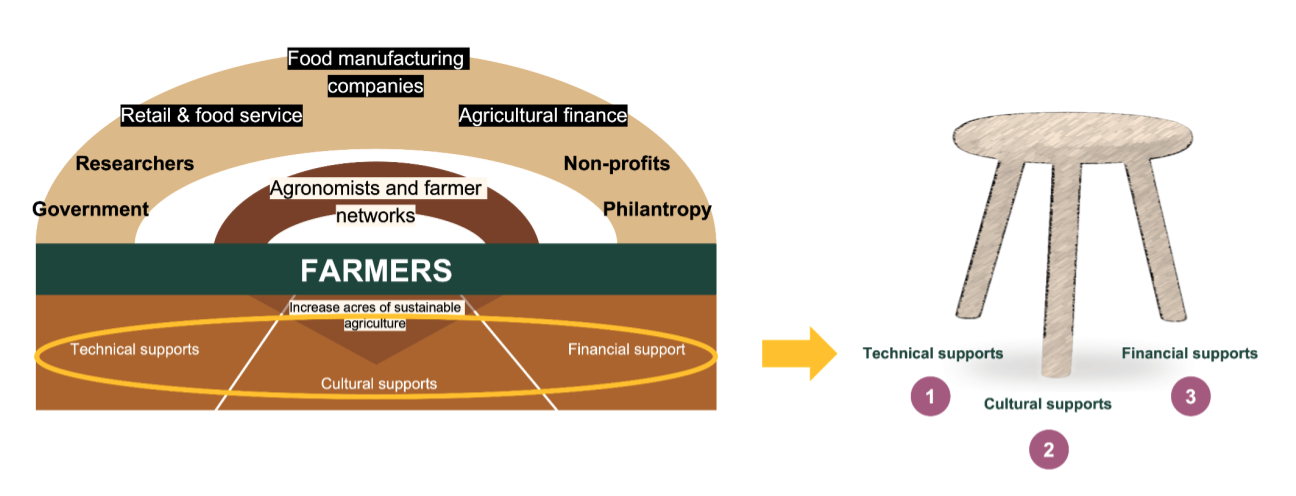

FoodBridge’s theory of change hinges on key partners including food manufacturing companies, retailers and agricultural finance institutions, with the ultimate locus of change being, of course, farmers. They grow our food and make the critical decisions that affect agricultural soils, nearby waterways and the climate. But the burden of that impact cannot and should not rest solely on the shoulders of farmers – it’s a shared responsibility that needs to recognize the underlying conditions that set farmers up for success or failure.

For farmer to make change, financial, technical and cultural supports are needed.

Financial supports can take the form of:

- Dollar per acre’ (typically $30-60) supports for practices like cover crops, reduced tillage and targeted fertilizer and pesticide use.

- Price premiums tied to quality (e.g., malting barley’s germination requirements) or practices (e.g., fungicide-free winter wheat), especially for small grains that enrich rotations otherwise dominated by corn and soy in eastern Canada.

- Building markets for diverse crops: we support organic sunflower and camelina oil manufacturers to more effectively structure themselves and promote the multiple environmental benefits of their products and are also working with pork producers and feed suppliers to assess and promote rye as a substitute for corn in feed.

- Subsidized seed for cover crops, where ROI materializes over the long term through improved soil, or for new, riskier crops such as fall-seeded barley.

- Low-interest loans for equipment enabling sustainable practices, like no-till seeders.

While the end goal is for prices that integrate externalities and pay the true cost of responsible production, financial supports from markets, governments and philanthropy are key in the short term.

Technical and cultural supports are often intertwined. In Quebec, a government-funded network of independent agronomists and ‘club conseils’ (advisory clubs) provide agri-environmental advice crops and farmer cohorts support peer learning on agri-environmental practices. FoodBridge convenes one such cohort of a dozen farmers and agronomists experimenting with premium fall barley—improving growing and storage techniques while strengthening relationships with malting and brewing companies. In Ontario, we partner with the Ontario Soil Network, a farmer-led initiative advancing soil health through peer-to-peer learning, field days, shop talks, and leadership training that builds local capacity.

We also work to improve measurement, reporting and verification, because despite some recent setbacks on sustainability targets, progress toward the data tracking required for transparency and credibility is urgently needed if we are to achieve meaningful impact.

Hard-learned Lessons

As FoodBridge enters our fifth year, a few learnings stand out:

- Financial viability is foundational. It enables farms and businesses to innovate and have impact. As we move beyond intrinsically motivated innovators to the middle majority, demonstrating the economic viability of environmentally sound practices becomes essential. This insight anchors our scenario-building work to model the ROI of different crop rotations in Quebec.

- It’s critical to recognize, applaud and support the work of others. One of our key agronomist partners, Cécile Tartera of Group Pro-conseil, says: ‘“My default question is simple: How can I help your project? It may seem counter-intuitive to protecting organizational interests, but generosity compounds and always leads to good results in the long run.”

- Communicate, communicate, communicate. Many problems stem from miscommunication and staying in close touch can prevent surprises and surfaces misalignment early, when it’s still fixable.

- The devil is in the (local) details. Our value-add often lies in local knowledge: funding programs, contract norms, trusted farmer leaders, and the nuances of regional agronomy and markets.

- Hold on to your values. This year I realized how building a team with aligned values (curiosity, collaboration, generosity, honest, transparency) that keeps its North Star firmly in sight helps weather changing partner, policy and funding winds.

Resilience in agriculture is built step by step, close to the ground, and with many hands. What we’re learning at FoodBridge is that progress comes from practical partnerships that meets companies where they’re at and farmers where they live. The goals may be big, but the work is everyday: aligning incentives, testing what works, sharing what doesn’t, and adjusting as we go. If we keep showing up with curiosity, transparency, and a focus on viable farms and companies, we can help make better farming systems a little more possible while delivering real climate gains.