The most affordable home is the one that doesn’t need rebuilding

As climate disasters grow more frequent and costly, the line between housing policy and climate policy is disappearing. Canada’s rush to build its way out of the affordability crisis risks recreating the same vulnerabilities that have already left thousands of homes uninsurable. In this article, Dustin Carey argues that affordability must be redefined: the cheapest home is not the one that costs less to buy, but the one built to last. True affordability, he contends, begins with resilience.

A Crisis of Affordability (and of Imagination)

Canada is in the midst of a deep housing affordability crisis, which has driven cost-of-living concerns to edge out all but the most oxygen-sucking issues from headlines, federal priorities, and public demands for action.

Waking up from decades of underperformance, recent government initiatives like Build Canada Homes and the Housing Accelerator Fund are working to move the needle on the housing construction deficit, while ambitious leadership from cities like Edmonton has pared back a regulatory quagmire that stymies cost-effective infill development. Setbacks, angular planes, shadow restrictions, parking requirements, second egresses, unit and height restrictions, and “growth-pays-for-growth mentalities”: these incremental zoning restrictions and fees have been added over the years to maintain safety and livability, but the cumulative effect has been a collapse of affordability and availability, particularly for younger generations like my own.

While the urgency of the housing crisis demands a rethink of many rules that restrict housing development, there is one area where our current regulatory paradigm has us sleepwalking toward future catastrophes.

The Overlooked Cost Driver: Climate Risk

One would think that during another year of rampant wildfires, climate change would feature prominently in the public headspace, but the proponents of denial and delay remain powerful. The fossil fuel lobby has proven adept at using cost concerns, the economic threats of the Trump administration, and partisan politics to champion tired advocacy points, artificially disconnecting climate change from other priorities.

2024 was the most expensive year on record for climate disasters in Canada. Events like the Calgary hailstorm, Jasper wildfire, Toronto floods, and the remnants of Hurricane Debby walloped Canada’s housing, insurance, and financial sectors, displacing people from their homes, saddling families with debt, and raising 2025 insurance premiums across the country to deal with historic losses. Meanwhile, 2025 has been the second-worst wildfire year on record, following closely on the heels of 2023’s devastating season, and has charred an area larger than Ireland. The Canadian Climate Institute estimates that over the last decade, the average cost of weather-related climate disasters each year has risen to the equivalent of 5-6% of annual GDP growth.

We cannot simply escalate the pace of home construction while relying on the same patterns that have left significant portions of Canadian households exposed to climate risk, especially as the climate hazards driving these losses continue to intensify.

When Insurance Walks Away, So Does Affordability

The consequences of inaction are already visible. In 2024, Desjardins, Quebec’s leading mortgage lender, announced that it would no longer issue new mortgages for properties within the 1-in-20-year floodplain, in response to recurrent significant riverine flood events in recent years. In 2023, State Farm, California’s largest single provider of bundled home insurance policies, announced it would stop cease issuing new home insurance policies in the state. While reticent to say so publicly, private conversations with members of Canada’s insurance industry hint that California’s present will be British Columbia’s future if we continue on our current path.

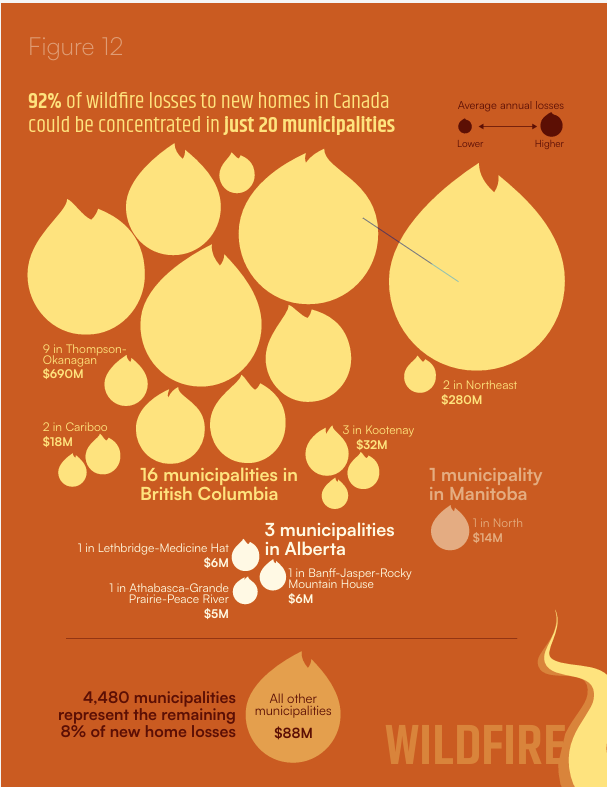

You cannot qualify for a mortgage in Canada without home insurance. Imagine the financial and political disaster that would come from investing billions in new home construction in central British Columbia – one of the fastest-growing regions of the country, which also accounts for the majority of new financial exposure in high-risk climate areas, according to the Canadian Climate Institute – if financial institutions effectively barred homebuyers from purchasing those homes.

Rethinking Affordability in a Warming World

Truly affordable housing can’t be disassociated from climate change: we must consider the costs of damage, displacement, and insurance. To address the housing deficit, we must think about access to mortgages and the losses that erase progress when homes are irreparably damaged.

The following changes to the housing industry are needed to build safeguards against escalating climate risks:

- How we disclose risk must change. It can be extremely difficult to determine if an existing home or planned development is at risk from floods, fires, or other hazards. Information should be easily accessible, public, and disclosed at critical points like the time of sale. In the United States, for instance, lot-level flood vulnerability is integrated into realtor.com. Such an approach may spark outrage from homeowners concerned about falling property values. However, it’s crucial to remember the disclosing risk doesn’t create it. Any resulting price adjustments would be corrections to overvalued assets predicated on missing information.

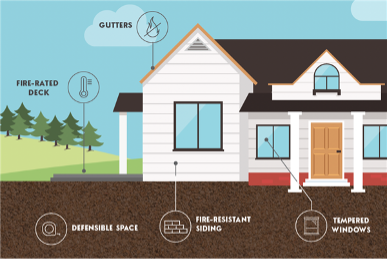

- How we build homes must change. Canada is a patchwork of building requirements, including federal and provincial building codes and municipal zoning rules. The process of updating federal codes to implementing changes at the local level is perhaps the most arduous in the world. The system is also highly resistant to change: even rapid-implementation solutions like hurricane clips, which can keep a roof attached during high-wind events at the cost of only a few hundred dollars, can take more than a decade to go from advocacy to adoption. Changes to building codes are sorely needed to both catch up to current realities and get ahead of future climate change impacts in the pipeline.

- Where we build homes must change. Land-use planning is among the most effective ways to manage hazard risk. Using disaster loss events and federal assistance data, a clear story emerges of the efficacy of the efforts and regulatory powers of Conservation Authorities to safeguard Ontarians by restricting high-risk development in floodplains. The Province of Nova Scotia embarked on a similar path of restricting coastal development before retreating and leaving leadership to municipalities like Halifax. In its Close to Home report, the Canadian Climate Institute demonstrates that a very small percentage of planned developments account for the vast majority of new financial risk. Building smarter yields huge dividends. To best leverage capacity, reduce political exposure, and maximize impact, high-risk development restrictions should be spearheaded by provincial governments.

- How we define housing affordability must change. Prime Minister Carney has emphasized the difference between capital and operating costs in government spending. The same distinction applies to housing. True housing affordability must encompass the full lifecycle cost of a home, where climate resilience and energy efficiency are the key determinants of financial stability for homeowners. A narrow focus on the initial purchase price ignores the severe and growing financial risks of climate hazards – including costly repairs, soaring insurance, and retrofits – as well as the burden of high energy bills from inefficient homes. To protect homeowners from unpredictable operating costs, affordability must be redefined to prioritize building homes that are both durable and efficient from the start.

The Home That Lasts

Housing built without regard for a changing climate is not affordable – it’s a liability deferred. From lot to landscape level, there are scores of effective options to meaningfully reduce the risk Canadians face. If we fail to build homes that can endure the conditions they will face, we will find ourselves paying for them many times over in repairs, insurance, and displacement. The most affordable home, and the only truly sustainable one, is the home resilient enough to stand the test of time.

Dustin Carey is a 2026 Clean50 Emerging Leader and has over 10 years’ experience working with municipalities to plan for and adapt to the impacts of climate change.