The Unfiltered Truth About Biotech Commercialization: How We Turned Microbes Into a Manufacturing Revolution

Canada has world-class scientists and bold biotech innovators—but too often, they lack the tools to scale. Roya Aghighi, CEO and Co-Founder of Lite-1, shares how her team developed breakthrough microbial dyes to replace toxic petrochemical colourants, only to face a hard truth: there was nowhere to manufacture them. In this piece, Roya reveals how Lite-1 turned infrastructure gaps into opportunities, building a national-scale solution through collaboration, creativity, and an unshakeable belief that breakthrough science deserves a path to market.

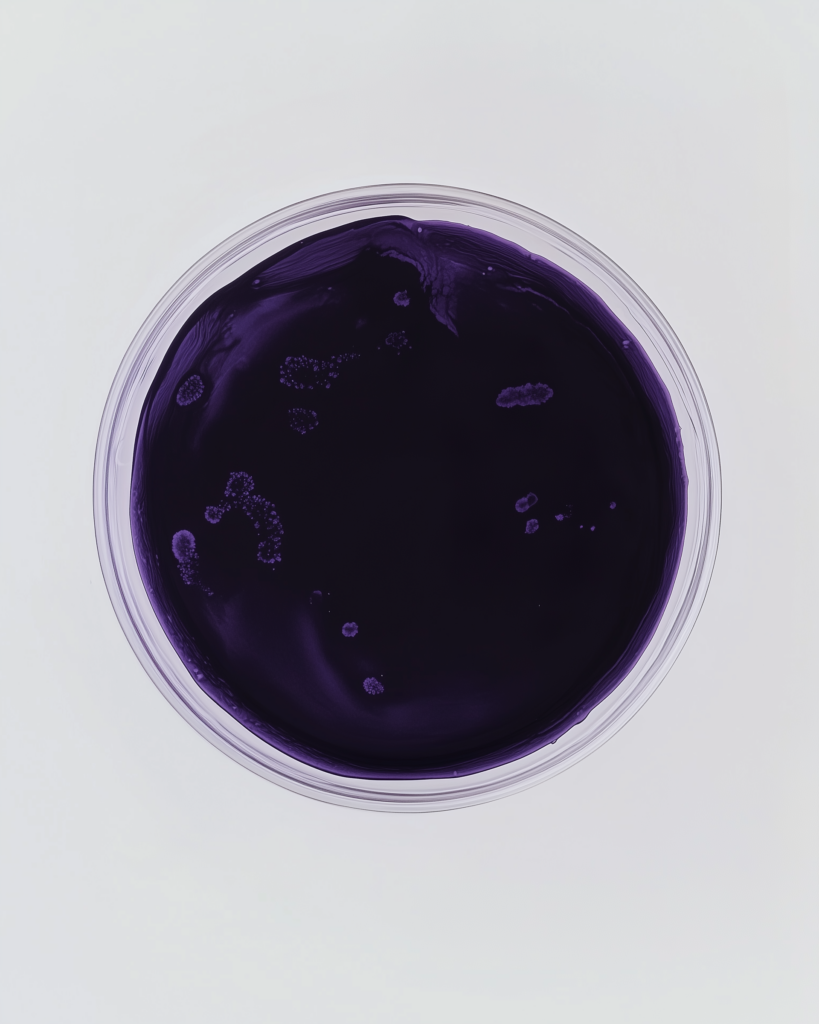

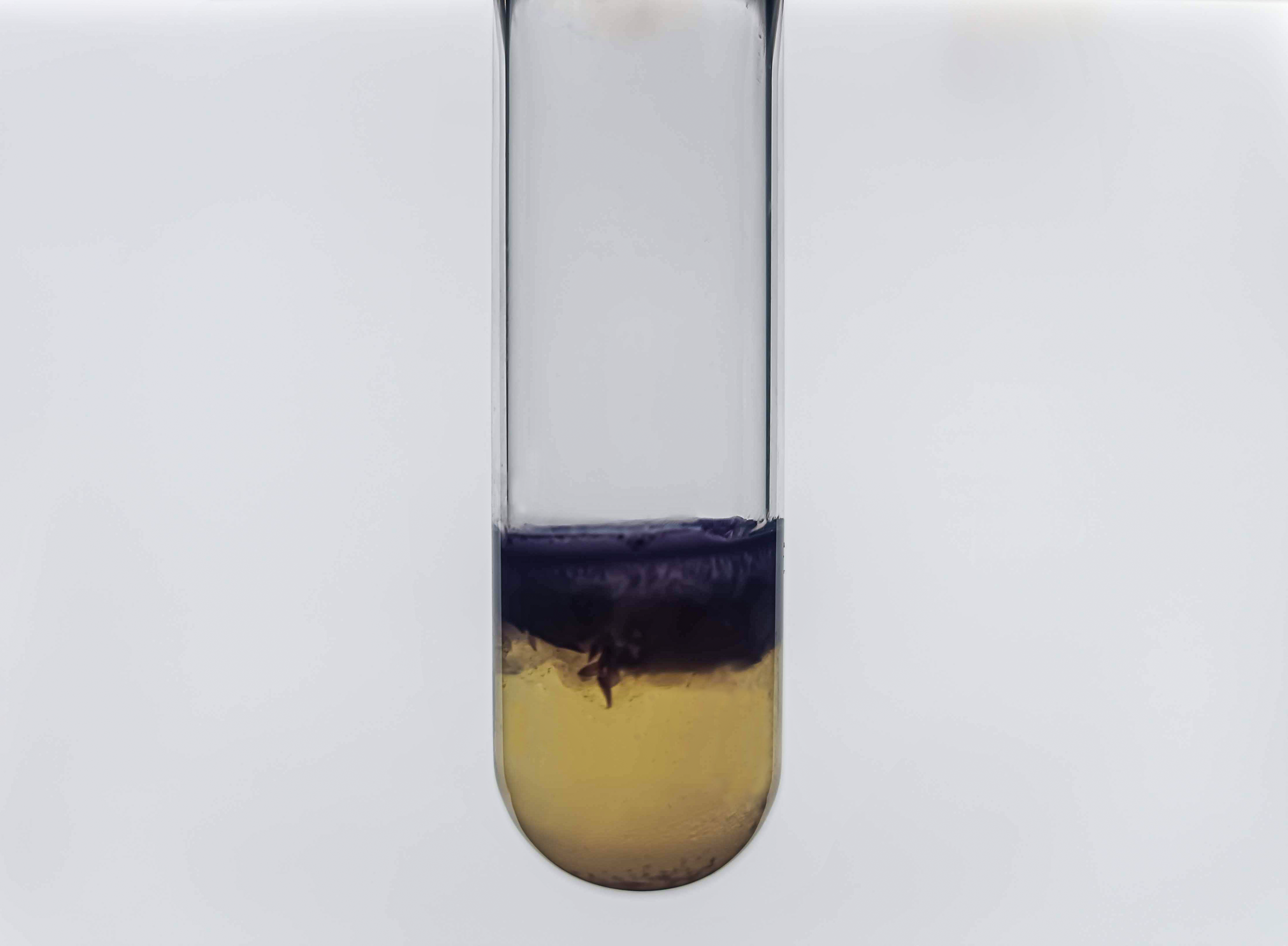

Picture this: You’ve cracked the science. Your microbes are producing vibrant, sustainable colors that could revolutionize a $175 billion industry. Investors are interested, customers are curious, and your lab results are promising. Then reality hits.

“Where exactly are we planning to scale this?”

We were so obsessed with fermenting perfect microbial colors in our lab that we forgot to ask the obvious: how do we scale this? When we finally looked up and searched Canada for biomanufacturing options, the truth hit like a slap: the infrastructure we needed was nowhere to be found. Nobody had built it. We were alone in a desert of ambition, and it was time to get scrappy.

This is the story of how we almost learned that lesson the hard way—and what it taught us about resourcefulness in commercializing breakthrough science.

The Infrastructure Desert

Here’s the ugly secret nobody tells you about biotech breakthroughs: cash isn’t everything. You can have a lab full of vibrant, world-changing colours, but without the tanks, pipes, and systems to scale them, you’re shouting into a void. The infrastructure to turn microbes into market gold? It didn’t exist. We learned that the hard way, and it’s why we’re fighting to build what Canada forgot.

At Lite-1, we had successfully developed microbial dyes at the 5-litre scale. Our colours were vibrant, our process was efficient, and brands were expressing real interest. But moving from 5 litres to the 50,000+ litres needed for commercial viability? That required specialized biomanufacturing facilities—fermentation tanks, downstream processing equipment, quality control systems—that we couldn’t just order overnight from some local shop. We first needed to prove other production volumes before considering approaching Commercial Manufacturing Organizations (CMOs).

We thought we had hit a wall, but it turns out this is Canada’s dirty laundry. Our nation’s biotech dreams are suffocating under a shameful lack of biomanufacturing muscle. While other countries roll out the red carpet for startups like us, Canada hands us a catch-22: scale up, but good luck finding the tools. We quickly realized we were solving our problem while also exposing a national challenge.

While other countries have invested heavily in shared biomanufacturing infrastructure, Canada’s biotech startups face a cruel catch-22: you need commercial-scale production to attract major investment, but you need major investment to build commercial-scale production.

“Canada’s biotech startups face a cruel catch-22: you need commercial-scale production to attract major investment, but you need major investment to build commercial-scale production.” – Roya Aghighi

Redefining Resources

Faced with this challenge, we had two choices: build our own facility (requiring millions we didn’t have) or get creative about what “resources” actually mean.

Most entrepreneurs think about resources in terms of capital, equipment, and facilities. But the most valuable resources are often the ones you can’t buy: relationships, expertise, and strategic partnerships.

Instead of trying to solve the infrastructure problem with money, we solved it with people.

The breakthrough came through our network. Through connections in the biotech community, we discovered the Verschuren Centre for Sustainability in Energy and the Environment in Nova Scotia. Unlike typical contract manufacturers, Verschuren operates on a collaborative model—they rent you equipment, but they also become your extended R&D team.

This partnership fundamentally changed our approach. Rather than viewing biomanufacturing as a commodity service to be purchased, we saw it as a strategic relationship that could accelerate our entire development timeline.

Building the Right Team

But finding the right facility was only half the solution. The other half was building a team that could thrive in this collaborative environment.

Here’s where most biotech companies get it wrong: they hire for credentials instead of mindset. Academic pedigree matters, but what matters more is finding people who see obstacles as puzzles to solve, not barriers to accept.

When we couldn’t find local biomanufacturing talent in Nova Scotia, we didn’t lower our standards or settle for remote collaboration. Instead, we sought team members who were willing to relocate, adapt, and work closely with our partners. We found scientists who were as excited about solving commercial challenges as they were about perfecting the science.

This mindset—that every problem has a solution if you’re willing to be resourceful—became our hiring filter. We looked for people who had navigated uncertainty before, who could work effectively in collaborative environments, and who understood that scaling biotech requires as much creativity as it does technical expertise.

The “It Has to Work” Mentality

Throughout this process, we operated from a simple conviction: this has to work. Not because we were naive about the challenges, but because the alternative—continuing to poison waterways with petrochemical dyes—wasn’t acceptable.

This mindset shifts everything. Instead of asking “Can we afford to solve this problem?” you ask “How can we afford not to?” Instead of waiting for perfect conditions, you create workable ones.

When we couldn’t find the ideal biomanufacturing setup in B.C., we didn’t pause our timeline or compromise our vision. We expanded our definition of what was possible. When traditional funding sources moved too slowly, we leveraged grants, partnerships, and collaborative agreements to maintain momentum.

Our mentality of “it has to work” isn’t blind optimism. It’s our way of refusing to accept that systemic problems—like Canada’s biomanufacturing gap—should not stop you from building solutions the world needs.

Lessons for Other Entrepreneurs

Our experience scaling Lite-1 taught us several lessons that apply beyond biotech:

- Infrastructure gaps are opportunities in disguise. What looks like a barrier often reveals underserved markets or partnership opportunities. Collaborating with the Verschuren Centre gave us a manufacturing lifeline. It provided us with a key piece of infrastructure that we couldn’t afford to purchase. They gave us tanks to rent, became our brain trust, our sparring partners, and our rocket fuel. They never made our relationship feel transactional. While giving us wings we didn’t know we needed.

- Your network is your most valuable asset. The connection that led us to Verschuren came through our extended network, not a Google search. Invest in relationships before you need them.

- Hire for resilience, not just résumés. Technical skills can be taught, but the ability to navigate uncertainty and maintain momentum through setbacks is rare. Forget hiring robots who check boxes and churn out plans. We built a crew of relentless puzzle-solvers—people who see roadblocks as invitations to outsmart the system. Our team invents, pivots, and thrives in the chaos of creation. That’s how you turn a biotech pipe dream into a world-shaking reality.

- Reframe constraints as creative challenges. Limited local infrastructure forced us to think nationally. Budget constraints prompted us to form collaborative partnerships, which ultimately strengthened our capabilities.

The Bigger Picture

Today, Lite-1 is scaling production through our partnership with Verschuren, developing new colors, and working with brands ready to replace toxic dyes and pigments with biologically based alternatives. But our journey revealed something bigger: Canada’s biotech potential is being limited by infrastructure gaps that collaborative models can help bridge.

“Canada’s biotech potential is being limited by infrastructure gaps that collaborative models can help bridge.” – Roya Aghighi

Organizations like Verschuren Centre are essential for individual companies; they help build a bioeconomy that can compete globally. When emerging companies can access shared infrastructure and expertise, breakthrough science reaches market faster.

For entrepreneurs facing their own infrastructure challenges—whether in biotech, cleantech, or any industry requiring specialized capabilities—remember that resourcefulness often matters more than resources. The biggest breakthroughs happen when you stop waiting for perfect conditions and start creating workable ones.

Sometimes the most revolutionary thing you can do is prove that the impossible is simply untested.